Welcome To

The James Museum from Home

Connect with us through curated content based on our collection. Explore art, movies, books, music, children’s activities and more. Each theme is freshly considered and developed by our curatorial and education teams. We invite you to discover a new way to experience the museum and learn more about our collection.

Theme: Wildlife

Explore visual art, movies, books, and family activities that celebrate wildlife and inspire us to care about the natural world.

Selected Artwork

Through paintings and sculptures, learn about six wildlife artists, their processes, and the stories they tell about animal biology and conservation.

Bonnie Marris

American, born 1951

Lunch

Grizzly bear and salmon

2016

Oil on canvas

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

Painter Bonnie Marris likes to get as near to her animal subjects as reason will allow. She believes getting up close to the animals, in the wild and on the canvas, reveals their individual personalities and moods. These intimate moments the artist depicts are often fun and playful.

Using a radial composition and almost no negative space, Marris locks you into the eyes of the bear. Notice how the simulated texture is hyper realistic at the center, then fades into implied detail and out of focus as the design disperses. This is how your natural eye sees images up close and in person. With technical mastery, the artist has rendered the bear in focus, immersing the viewer into the scene.

The grizzly bear is considered an umbrella species. Species selected for this conservation-related list are ones whose protection and conservation safeguards other species within their ecosystem. Grizzlies need large, wild spaces to survive. Protecting these spaces for bears by limiting mining, oil exploration, development, and logging, also protects space for other living species including elk, deer, mountain goats, mountain lions, beavers, birds, insects, plants, and fungi. All of which play their own role in the health of the ecosystem. It adds to a simple biological truth that everything in the natural world is connected.

Michael Coleman

American, born 1946

Prince of the Okavango

Common warthog

2010

Bronze (11/30)

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

Coleman has cleverly named this warthog the Prince of the Okavango. The Okavango Delta is a vast and unique ecosystem in the middle of the Kalahari Desert in northern Botswana. It has been called a miracle of nature.

The Kalahari Desert covers Africa’s southern interior, forming the largest continuous stretch of sand in the world. It is called a “thirstland” because for much of the year there is no standing water. Once a year, it is rainy season in the Angola highlands, about 1,000 miles north of the Okavango Delta. Typically, the rain would flow down rivers, eventually leading out to sea. Due to a series of topography quirks, this does not happen in the region. Instead, the water spills out onto the Kalahari Desert, a true phenomenon, creating the largest inland delta in the world.

It takes months for the water to make the long trip to the desert, and because of this, the water reaches the delta during the dry time of year. It is a welcomed reprieve to the thirsty land and animals and is a lifeline to the inhabitants of the area, including the people. During times of drought, hundreds of thousands of wildlife perish. Much of Africa’s large mammals can be found at the delta when the water is present, including the warthog, depicted here. This animal is known for its fearless character and often stands up to its predators, possibly the reason why the artist dubbed him a Prince.

According to National Geographic, “While the Okavango Delta is protected within Botswana, the greater Okavango Basin, which includes the critical rivers and lakes that supply the delta, are not. These source waters are under increasing threats from deforestation, uncontrolled fire, the rising commercial bushmeat trade, and unchecked development. If these waters remain unprotected, the future of the Okavango Delta is at risk.”

Sherry Salari Sander

American, born 1941

The Game of Alpha

Gray wolf

1999

Bronze (9/35)

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

A wolf pack is a complex social unit. The leaders are the parents, often called the alpha male and alpha female. It is common to see a pack roughhousing, like depicted in this bronze sculpture. This could be the alphas harassing the less mature wolves, in prelude to their dispersal from the pack to start their own families. It could also be the younger wolves instigating play time. Even with playtime, it’s a continued learning process for the juveniles.

To witness this behavior, all artist Sherry Sander needs to do is look outside her window. She lives and works on a 300-acre ranch in the Montana countryside. She and her husband have made it their life’s work to protect the land and create a safe haven for all living things. “It’s just National Geographic here every day,” Sanders says, “a constant parade of wildlife.”

Wolves are one of the most misunderstood and persecuted animals. Considered a keystone species, their presence is critical to the survival of other species within the ecosystem, making them essential to biodiversity. A fascinating example of this is what scientists have been learning from wolves in Yellowstone National Park.

In the 1920s, the gray wolf was hunted with such determination that they were eradicated from Yellowstone. By the 1930s, scientists were already worried about the adverse effects this was having on the ecosystem. With no check on the elk in the area, the park had been overgrazed, prompting a string of disappearing plant and animal species. Not until 1995 were wolves reintroduced to Yellowstone.

While the wolves do hunt elk, the most significant factor is that the presence of the wolves changes the elks’ behavior. Forced to be on the move to avoid danger, the elk were no longer able to graze in one area. Their constant movement gave the vegetation a chance to recover. This led to more birds, foxes, rabbits, bears, beavers, and so on, all of which have their own positive effect on the environment. The new growth along the river stabilized the riverbanks, creating an entire, healthy marine ecosystem. Adding only 30 gray wolves to the park in 1995 triggered a trophic cascade that some credit for saving Yellowstone.

John Banovich

American, born 1964

Fleeing Rwanda

2002

Oil on Belgian linen

Art Spotlight

By: Jason M. Wyatt | Collections Manager

On loan from a private collection, “Because of Leonard.”

In this painting, we see a family of mountain gorillas emerging from the jungle to cross a river, escaping the ravages of civil war in Rwanda. According to the artist, “War produces casualties both human and animal, and the gorillas are no exception. Sounds of war can force them to flee their home territory into new and unfamiliar places, putting severe stress on the entire troop.”

Since the discovery of mountain gorillas in 1902, the population has been decimated by disease, habitat loss, poaching and war, bringing them to the brink of extinction. Today, thanks to conservation efforts, there are about 1,063 mountain gorillas in the wild.

Two distinct populations of mountain gorillas exist in Africa. The first population resides in three national parks within the volcanic Virunga Mountains of central Africa: Mgahinga Gorilla National Park in southeastern Uganda, Volcanoes National Park in northwest Rwanda, and Virunga National Park in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. The second population resides in the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in southwestern Uganda.

Mountain gorillas are very susceptible to human respiratory illnesses. Tourists to the region are asked to stay 23 feet away from the gorillas and to avoid contact when possible. Researchers discovered that this barrier was broken 98% of the time. Of that time, humans broke the barrier 60% while gorillas broke the barrier 40% due to their curiosity. Scientists believe the COVID-19 virus can be spread to the gorillas, so Rwanda and Democratic Republic of the Congo have closed the parks to tourism, cutting off much needed income. As a result, scientists worry there will be an increase in poaching. Uganda still allows tourists to see the gorillas after a strict health screening and quarantine process.

Nancy Glazier

American, born 1947

Dust Devil

American bison

1996

Oil on canvas

Art Spotlight

By: Jason M. Wyatt | Collections Manager

Raised in Wyoming, artist Nancy Glazier is no stranger to the wonders of the American bison. Her painting expertly brings to life one of the most recognizable symbols of the American West that faced extinction in the late 19th century. Standing at six feet tall with a length of up to 12 feet and a weight of 2000 pounds, the male bison is the largest land mammal in North America.

At the time Europeans arrived in the 16th century, there were an estimated 30-60 million bison roaming North America. Herds ranged from what is now northern Mexico up through the United States into Canada and reaching as far east as Georgia and Pennsylvania.

By the late 19th century, the survival of the bison was uncertain due to overhunting by non-native people. The widespread slaughter of bison was sanctioned by the U.S. government, eliminating a vital resource to many Native American groups. Destroying this resource allowed settlers to take control of native lands, as food sources became scarce and native groups were forced to migrate for survival.

The opening of the American West by railroads across the Great Plains made it easier for hunters to slaughter hundreds of bison at a time from the luxury of a railcar. Some railroad companies promoted the sport of “hunting by rail”, with the U.S. government providing incentives like free ammunition. Hunters took only the desirable parts of the bison like the hides for clothing and the tongues, considered a delicacy at fine restaurants, leaving the carcasses where they fell. Once the meat rotted off the carcasses, the bones were collected by settlers and sold to be used in fertilizer, fine bone china, and sugar refinery. Between 1870-1874 an estimated 7.5 million bison were killed as thousands of hunters flooded west to make their fortunes.

In 1889, conservationist William Hornaday estimated the American bison population to be less than 1,100. He concluded there were 85 free ranging, 200 in the Yellowstone National Park herd, 550 at Great Slave Lake in Canada, and 256 in zoos and private herds. Hornaday is credited with preserving the species through the American Bison Society, which he helped to establish in 1905. In 1919 the organization successfully reintroduced nine herds into the wild. Today there are an estimated 500,000 bison living in North America, though a far cry from the original numbers that once roamed the continent.

Geoffrey Smith

American, born 1961

Dancing Crane

Sandhill Crane

2006

Bronze (9/98)

Art Spotlight

By: Jason M. Wyatt | Collections Manager

Florida artist Geoffrey Smith’s sculpture of a Sandhill Crane captures a moment the artist has seen many times in the wild. With wings extended, cranes often leap into the air, performing a dance to claim territory, establish social relationships, and reaffirm the lifelong bond between a breeding pair. Yearlings learn basic movements by watching the adults, perfecting their own dances over time. Without precision, a crane’s dance may affect its ability to find a mate and establish strong social bonds.

There are five subspecies of Sandhill Cranes. The Lesser and Greater Sandhill Cranes are migratory birds with a range from eastern Siberia through Canada and the United States, and into northern Mexico. The Mississippi Sandhill Crane is non-migratory and is found along the northern Gulf Coast. The Florida Sandhill Crane, also non-migratory, is found throughout the Florida peninsula and southern Georgia. The Cuban Sandhill Crane, another non-migratory subspecies, is found throughout the Cuban archipelago.

The Greater Sandhill Crane, largest of the subspecies, faced extinction from overhunting in the 20th century. Their numbers dropped to about 1000 by 1940 but with hunting limitations put in place their numbers have grown to over 100,000. The three non-migratory subspecies have all faced obstacles to their survival in recent years. Due to habitat loss, the Mississippi Sandhill Crane is classified as critically endangered with just over 100 individuals left in the wild. Florida Sandhill Cranes are protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act and are designated by the state as threatened. This subspecies was originally found along the northern Gulf Coast but habitat loss in Texas, Alabama and Louisiana has confined the birds to Florida and Georgia. Here in Florida, their habitat is quickly diminishing due to the use of prairies and wetlands for construction. Little is known about the Cuban Sandhill Crane population but a study in the late 1990s estimated their numbers to be around 600 individuals in the wild. The Lesser Sandhill Crane has been the most resilient of the subspecies with a current population of over 400,000. Like all the subspecies, they too are faced with an increasing loss of habitat.

Books

The James Museum Book Club Recommends…

American Serengeti: The Last Big Animals of the Great Plains

By Dan Flores

Less than 200 years ago, America’s Great Plains offered one of the grandest wildlife spectacles in the world, even attracting wealthy Europeans on elaborate safaris. That’s just one of the fascinating things I discovered reading Dan Flores’ book, American Serengeti.

Flores tells us what happened to pronghorns, coyotes, wild horses, grizzles, bison, and wolves and asks provocative questions about morality and human behavior. Unfortunately, only the coyotes prospered. Efforts to kill them caused them to reproduce at a greater pace and now there are coyotes pretty much everywhere—even here in St. Petersburg.

To me, the saddest of these stories is the mass slaughter of millions of American bison in the 1800s, when they were driven nearly to extinction. Demand for bison hides, sport shooting and drought all played a part. Today there are efforts to “re-wild” a portion of the Great Plains to bring back the bison, and wolves have been reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park.

You can see bison at places such as Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota and Badlands National Park and Custer State Park in South Dakota. If you’re lucky, you might even spot one on Paynes Prairie Preserve here in Florida, near Gainesville.

Learn More

This Montana-based nonprofit is working to create the largest nature reserve in the continental United States. Explore their educational resources and efforts to restore habitats and wildlife.

Learn about two different perspectives on the restoration of Bison in Montana

Conservationists in the US state of Montana are creating an “American Serengeti” by buying up ranch land, pulling down fences and creating a vast swathe of territory for bison to roam. But ranchers are opposed to the idea saying it is a threat to their communities and their livelihoods. (3:45 min)

The American bison was once on the brink of extinction. Thanks to two ranchers in the 1800s, the ancestors of these remaining few survived. Now, the American Prairie Reserve is working to restore a vast amount of prairie to its natural state. This film follows the process of moving these bison and the challenges encountered along the way. (12:18 min)

Movies

Explore feature-length and short films that examine human and wildlife interactions, conservation issues, and scientists working to protect animals and the environment.

Feature Films

Into the Okavango (2018)

From National Geographic Films, this stunning documentary chronicles a team of modern-day explorers on an epic four-month, 1,500-mile expedition across three countries to save the river system that feeds Africa’s Okavango Delta, one of our planet’s last wetland wildernesses. Not Rated; 94 min.

Grizzly Man (2005)

Pieced together from actual video footage, this remarkable documentary examines the calling that drove a man to live among a tribe of wild grizzly bears on an Alaskan reserve. A devoted conservationist with a passion for adventure, Timothy Treadwell believed he had bridged the gap between human and beast. When one of the bears he loved and protected tragically turns on him, the footage he shot serves as a window into our understanding of nature and its grim realities. Rated R; 104 min.

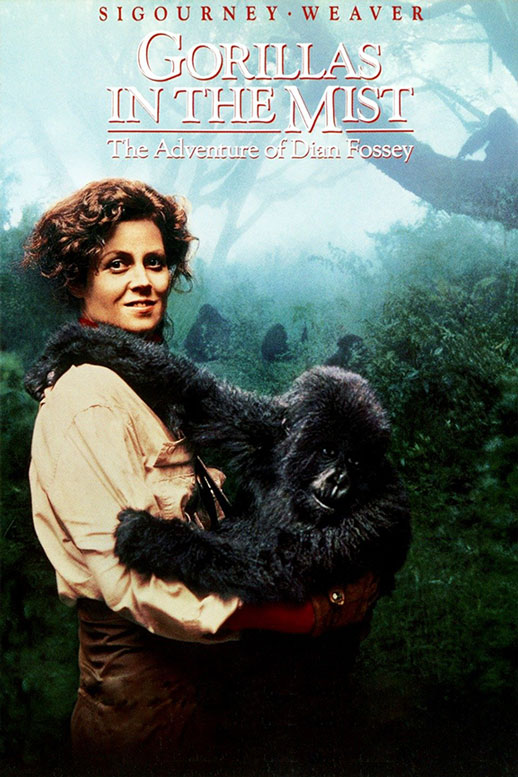

Gorillas in the Mist (1988)

This classic film is an adaptation of wildlife expert Dian Fossey’s autobiography. Fossey leaves the United States for Africa, where she studies the gorillas of Rwanda and Uganda. As she develops a bond with the animals, she also becomes wary of the poachers who prey on them. Fearing that the gorillas will go extinct if humans continue to hunt them, she organizes a defense league to protect the animals, putting herself in a perilous situation. PG-13; 129 min.

Short Films

In this award-winning short documentary, naturalists Erv Nichols and Sandra Noll discover love, adventure, and a new life while following the epic migration of the sandhill cranes, from the Southwest U.S. to north of the Arctic Circle in Alaska. (7:10 min)

What do bovids, bridges, and the West have to do with American art? Find out through fascinating stories from curators at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Zoo. (5:25 min)

Take a journey into the world of wolves with intimate and rarely seen footage of one of North America’s greatest predators. A moving soundtrack of Native American music adds a deeply poignant element to this documentary. Filmed in locations including Yellowstone National Park, Montana, Idaho, Alaska and Quebec, Wolves offers hopes and inspiration. (40 min)

Fewer than 20 grizzly bears remain in the North Cascades. Wildlife filmmaker and ecologist Chris Morgan interviews Washington State residents about what they know about their elusive neighbors. He helps bust some common myths and raises the question of whether cohabitation is possible with one of the state’s critically endangered species. (7:51 min)

Podcasts

This series of award-winning podcasts explores the American bison through a range of voices and perspectives. The United States named bison its national mammal, but we still haven’t decided if we’re ready to restore them as wild animals on the American landscape. Could we ever live with wild, free-roaming bison again? Should we try? Why, or why not?

Family Activities

Story Time

Read along with these colorful and engaging wildlife stories.

A Little Bit Brave

By Nicola Kinnear

Art Activities

Get creative with inspiration from wildlife artists and artwork in the museum’s collection.

Animal Mask

Learn how to make your own animal mask out of a paper plate with Stacy Stockdale, Manager of Youth & Family Programs.

Draw a Bison

Learn how to draw a Bison from simple lines and shapes with Annie Dixon, Teen Volunteer.