Welcome To

The James Museum from Home

Connect with us through curated content based on our collection. Explore art, movies, books, music, children’s activities and more. Each theme is freshly considered and developed by our curatorial and education teams. We invite you to discover a new way to experience the museum and learn more about our collection.

Theme: Journey

Travel with us on imagined journeys westward through works of visual art, books, movies, and creative activities for families.

Selected Artwork

Discover paintings and sculptures that tell stories of movement and migration through the eyes of artists.

Robert Griffing

American, born 1940

Another Broken Treaty

2013

Oil on canvas

Art Spotlight

By: Jason M. Wyatt | Collections Manager

In this painting by Robert Griffing, we see a small group of Eastern Woodland tribal members watching from behind rocks as Anglo men drive a wagon through the forest. The title, Another Broken Treaty, alludes to the fact that the white men are trespassing on native land. When we look at the mother and child, we cannot help but wonder if it’s disappointment as she wipes away tears on the child’s face or concern as she covers the child’s mouth so as not to be discovered. We also know the end result; this group will be forced from their land as resistance will mean certain death.

A treaty is a document that outlines the peaceful intentions between two sovereign nations, in this case, the United States and specific native tribes. Between 1776 and 1871, when the U.S. government stopped recognizing native tribes as sovereign nations, there were 370 treaties negotiated. The most common features of these treaties were the guarantee of peace, protection from domestic and foreign enemies, and most importantly, the creation of boundaries between the two nations. In order for non-native people to enter sovereign tribal lands, they needed to carry an official passport. Without one, they were trespassing.

As the non-native population exploded along the eastern seashore, so did the need for land. Treaties were broken as settlers began migrating west and invading native lands. Some native groups hoped to slow the invasion by attempting to renegotiate the treaties, selling, or giving up portions of their lands. Most of these attempts were unsuccessful, so tribes began to journey west to escape an uncertain future.

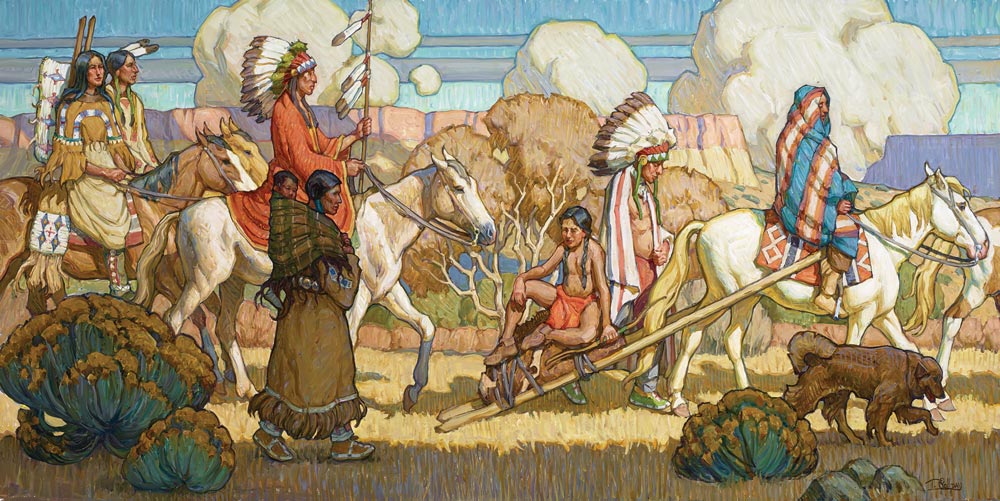

Tim Solliday

American, born 1952

Migration

2015

Oil on canvas

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

In this painting, a band of Native Americans migrate across the Great Plains, the flatlands east of the Rocky Mountains, in the center of North America. It spans from present-day Canada down to present-day Texas. The dozens of native tribes who historically inhabited this region are known as Plains Indians. Though referenced as a single unit, these tribes varied, sometimes dramatically, in lifestyle due to the diverse climates of the vast area. One thing they had in common was hunting bison.

Before horses were reintroduced to the North American continent in the 16th century, the Plains people were pedestrian hunters, most of them maintaining a combination of nomadic and sedentary lives. Spring and fall were dedicated to planting and harvesting crops, while summer and winter were spent traveling, on the hunt for bison. The migratory cycle of the Great Plains Indians was a journey through lands and seasons.

When horses became widely available in the 1700s, many of the Plains tribes became exclusively nomadic hunters. They calibrated their movements to the bison herds and regarded the animal and their migration patterns as sacred. For much of the year, they lived in small family bands, and they gathered in large camps only in the summer for celebrations, trading, and communal hunts. Almost constant movement was necessary for groups like this one, to ensure the survival of their horses. After a few days, the horses would have grazed an area to nothing, obliging the group to journey on to the next water source. To move their goods, they used sled-like structures called travois, pulled by horses or dogs.

The multiple figures in the tight foreground, and the long, progressive composition give this painting the feeling of forward motion. Painter Tim Solliday expresses the narrative of the journey from left to right, similar to the storytelling on black-figure pottery by the Ancient Greeks. The artist’s flat renderings, emphasized contours and whimsical colors are inspired by his appreciation of illustrative art. For these panoramic scenes, Solliday also cites the classic principles of mural paintings, especially inspired by the California mural art of the WPA Federal Arts Project of the 1930s and ‘40s.

Oscar Edmund Berninghaus

American, 1874–1952

Stagecoach Through the Missouri Hills

1938

Oil on canvas

Art Spotlight

By: Emily Kapes | Curator of Art

In 1857, the federal government awarded a $600,000 annual contract to the American Express Company to establish and operate the first transcontinental stagecoach line, called the Overland Mail. Within a year, men, horses and coaches were procured, and scores of way stations built along the route. U.S. Mail coaches began service for letters as well as passengers on a semiweekly basis in 1858, running between St. Louis and San Francisco. Regular service continued until the Civil War started in 1861.

The long journey west was crowded, bumpy, and sometimes dangerous, and it took about three weeks, even in ideal weather. Packed full of people and bags of mail, the coaches kept moving all day and night, except for short intervals to change out horses. Travelers paid significant money to ride, with the journey from Missouri to California costing $200, plus meals.

The stagecoach was the main form of westward transportation before the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869. Even as the railroad network grew larger and more comprehensive, stagecoach connections to small and isolated communities continued to supplement passenger trains into the early 1900s. This painting shows how a coach passing through a small, western community would have been exciting.

Vic Payne

American, born 1960

Into the Wild

2014

Explorers of the West Series

Bronze (3/12)

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

This monumental sculpture depicts explorer John C. Fremont (1813–1890) and frontiersman Christopher “Kit” Carson (1809–1868) during their 1843–1844 expedition. Fremont was a topographer for the United States government, on a mission to map out the Oregon Trail, the Great Basin (the region covering most of present-day Nevada), and other areas of the West. Carson was many things, among them a mountain man with intimate knowledge of the geography and the people of the region due to his many years and ventures as a fur-trapper.

The two men met by chance on a steamboat, and Fremont hired Carson to be his expedition guide. Carson’s knowledge and skills were invaluable and found to be vital to their success. The maps and guidebooks made possible by these journeys, for better or for worse proved crucial to the expansion of the west. Their union achieved national fame, and Kit Carson’s exploits became popularized (and fictionalized) in dime novels. As notable figures of westward expansion, their names are not without controversy. They were both directly involved in Indian wars and massacres. Most discussed today was Carson’s involvement in a brutal campaign against the Navajo, which led to the Long Walk of the 1860s.

In this sculpture, the artist takes us on a journey back to when Fremont and Carson were navigating the waters of the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers. Together, they would go on to venture into uncharted territory, a perilous, overland journey full of triumphs and tragedies.

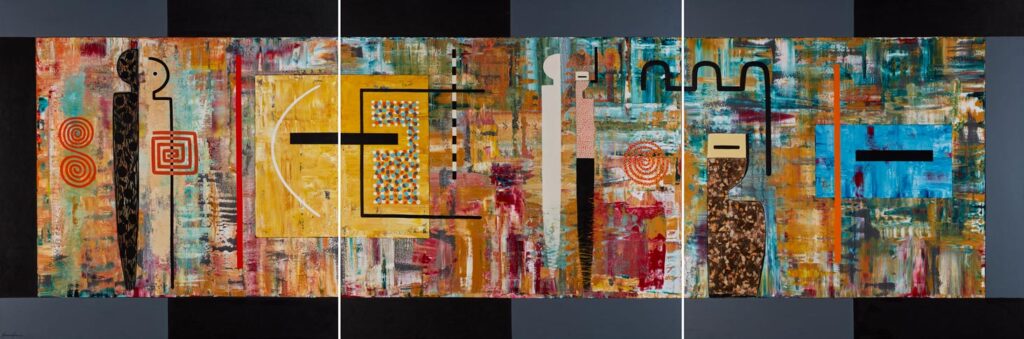

Dan Namingha

Tewa-Hopi, born 1950

Passage III

1999

Acrylic on canvas with paper collage

Art Spotlight

By: Emily Kapes | Curator of Art

Imposing in size and complex in design, this large triptych* represents a spiritual journey. The abstracted imagery includes symbols and suggestions of elements from the artist’s Hopi culture. Namingha expresses his culture in fragments to keep the most sacred doctrines and rituals within the Hopi people.

The Hopi have maintained involved religious and mythological traditions for centuries; part of their belief system includes the complex history of migrations of their people. Entitled Passage III, the squares and rectangles are important motifs to Namingha as they represent passageways to other worlds; in this instance, these are portals between the physical world and the spiritual world. The spirals signify human migration and the summer and winter solstice.

In the right panel, an outlined brown and cream paper collage represents the head and torso of a Butterfly Maiden, or Palhik Mana. A symbol of peace and fertility, she wears a terraced headdress, suggested by the vertical black line that curves and continues in waves to the center panel. Significant colors represent the four cardinal directions, important for orientation during journeys; yellow is north, red is south, white is east, and blue is west.

*A triptych is a work of art in three panels, meant to be displayed together.

Ralph Oberg

American, born 1950

Crossing the Glacier

Barren-ground caribou

2010

Oil on canvas laid on foamcore

Art Spotlight

By: Jason M. Wyatt | Collections Manager

Artist Ralph Oberg captures the image of caribou migrating across mountainous terrain. The three adults in this painting are Barren-ground caribou, a subspecies made up of nine distinct herds. Each herd can number in the tens of thousands, and are found throughout northern Alaska, the Northwest Territories of Canada, Nunavat, and up to Baffin Island.

Caribou spend most of their lives on the move, migrating more than any other land animal. The need to find food dictates when Barren-ground caribou migrate between their winter and summer ranges. In winter, the herds separate based on gender and settle into forests where they can shelter from the harsh weather and feed on lichens. By spring, the herd comes together again and migrates to the calving grounds where the cows leave the herd once more to give birth. By summer, the cows and their calves rejoin the bulls on the tundra to eat the plentiful grasses to prepare for the winter.

For some of the Barren-ground caribou subspecies, like the Porcupine caribou herd, winter and summer ranges can be 400 miles apart. By tracking this migration pattern with satellites, biologists discovered that this herd actually journeys close to 3000 miles annually.

Books

The James Museum Book Club Recommends…

The Essential Lewis and Clark

Landon Y. Jones, editor

The original American road trip was the Corps of Discovery’s 8,000-mile journey from St. Louis, Missouri, to the Pacific Ocean and back in 1804 to 1806. Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark kept journals describing their expedition, which Landon Jones has edited and annotated into an easily read format (although he kept their creative spelling).

Stephen Ambrose’s book Undaunted Courage is the classic story of this adventure, and not to be missed, but there is something special about delving into the original journals of these explorers. Reading about the Corps’ encounters with grizzly bears, flash floods, rapids, friendly and hostile Indians, and near starvation, makes you feel like you are right there. I enjoyed learning more about Lewis and Clark as well as Sacagawea.

One of the best parts about delving into the Corps of Discovery’s adventure is that you can take your quest on the road. You can still walk in the group’s footsteps and see many of the original artifacts at museums and discovery centers across the west. Two of the best sites I have visited include reconstructions of the forts where the expedition wintered—Fort Mandan near Bismarck, North Dakota, and Fort Clatsop, near Astoria, Oregon.

Learn More About the Lewis & Clark Expedition

Explore stories, places, and the people involved in Lewis & Clark Expedition. Their voyage covered more than 8,000 miles in less than two-and-a-half years. It had resounding effects throughout American science and history, and disrupted the lives of countless Native Americans throughout North America.

Produced by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, this searchable website includes journals, maps, illustrations and more.

More Books

The Journey of Crazy Horse

By Joseph M. Marshall III

Many know Oglala leader Crazy Horse as a peerless warrior who brought the U.S. Army to its knees at the Battle of Little Bighorn. But to his fellow Lakota Indians, he was a dutiful son and humble fighting man who—with valor, spirit, respect, and unparalleled leadership—fought for his people’s land, livelihood, and honor. In this fascinating biography, Joseph Marshall, himself a Lakota Indian, creates a vibrant portrait of the man, his times, and his legacy.

Being Caribou: Five Months on Foot with an Arctic Herd

By Karsten Heuer

In 2003, wildlife biologist Karsten Heuer and filmmaker Leanne Allison embarked on a five-month research journey to follow the 2,000-mile migration of a herd of caribou. From Old Crow, Yukon, they traced the ancient paths and primordial rhythms of the herd through Canada and over the border to the U.S. Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The couple travelled on foot and by ski through unforgiving landscapes, fording swift and deadly cold rivers, and encountering ravenous grizzlies who tracked them as prey. Both a rousing adventure story and a sober ecological meditation, Being Caribou vividly conveys this magnificent animal’s world.

Movies

These feature length films will transport you on perilous adventures across the West, from Monument Valley to the Oregon Trail, and into the Arctic tundra.

Feature Films

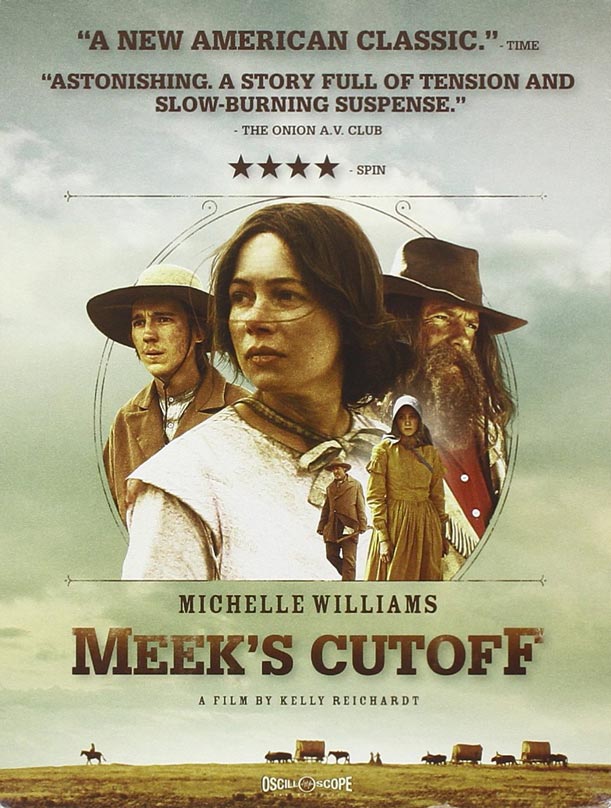

Meek’s Cutoff (2010)

The year is 1845, the earliest days of the Oregon Trail, and a wagon train of three families has hired mountain man Stephen Meek to guide them over the Cascade Mountains. Claiming to know a shortcut, Meek leads the group on an unmarked path across the high plain desert, only to become lost in the dry rock and sage. Over the coming days, the emigrants face the scourges of hunger, thirst, and their own lack of faith in one another’s instincts for survival. PG; 104 min.

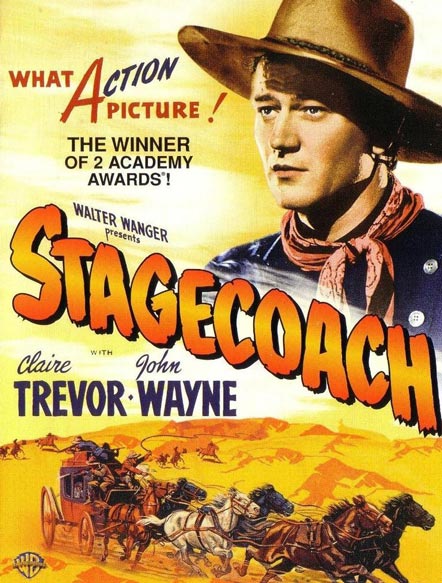

Stagecoach (1939)

John Ford’s landmark Western revolves around an assorted group of colorful passengers aboard the Overland stagecoach bound for Lordsburg, New Mexico, in the 1880s. An alcoholic philosophizer, a lady of ill repute, and a timid liquor salesman are among the motley crew of travelers who must contend with an escaped outlaw, the Ringo Kid, and the ever-present threat of an Apache attack as they make their way across the Wild West. NR; 99 min.

Being Caribou (2005)

This documentary features husband and wife team Karsten Heuer (wildlife biologist) and Leanne Allison (environmentalist) as they follow a herd of 120,000 caribou on foot across the Arctic tundra. In tracking the herd’s migration, the couple hopes to raise awareness about threats to the caribou’s survival. Along the way they brave extreme weather, icy rivers, hordes of mosquitoes, and a hungry grizzly bear. Dramatic footage and video diaries combine to provide an intimate perspective of an epic expedition. NR; 72 min.

Family Activities

Story Time

My Papi Has a Motorcycle

By Isabel Quintero

Illustrated by Zeke Peña

Art Activity

Colorful Line Drawing

Get creative with inspiration from artists and artwork in the museum’s collection.