Welcome To

The James Museum from Home

Connect with us through curated content based on our collection. Explore art, movies, books, music, children’s activities and more. Each theme is freshly considered and developed by our curatorial and education teams. We invite you to discover a new way to experience the museum and learn more about our collection.

Theme: Community

What does community mean to you?

Explore creative offerings by artists, writers, and filmmakers who reflect on ways that human connection, shared experience, belonging, support, and healing can come through community bonds.

Selected Artwork

Discover how painters, sculptors, and jewelers express ideas about community, collaboration, friendship, traditions, and more through their creative works.

Charlie Dye

American, 1906-1972

Dinner Music

Late 1950s-early 1960s

Oil on canvas

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

A cattle drive is the process of moving cattle from one place to another. During the height of the cattle boom, 1865–1885, a typical long drive consisted of ten cowboys moving 2,500 cattle from Texas to Wyoming, a 1,200-mile journey. It would not be an overstatement to say that this was excruciating work. It was four straight months in the saddle, seventeen-hour days, seven days a week, for low wages and in dirty, dangerous conditions.

Normal, everyday hardships on a drive could have included riding through rain and hail, a clap of thunder triggering a stampede, lice, quicksand, violent or tense conflicts with Native Americans, incessant flies, boils, persistent hunger, putting down horses, rheumatism, freezing nights, fatalities, and of course, wrangling cattle. The cowboys saw each other at their best, their worst, and their most vulnerable. This combination created a powerful camaraderie and special bond among the men. The feeling of being home on the range was possible despite the hardships, because of the communal bonds developed between the cowboys.

A welcomed reprieve to the grueling day would have been the cook’s bell, alerting the crew that it was mealtime, as depicted in this painting. The cook was the first one awake, he packed and drove the wagon, prepared three hot meals a day, and he was the unofficial doctor, tailor, barber, and mediator. He was often the last to go to sleep, pointing the chuck wagon’s tongue toward the North Star to give the trail boss a sure compass in the morning.

During cattle drives, the chuck wagon was the community center, where everyone gathered. The chuck wagon held everything needed for the long voyage. The first was a repurposed Army wagon, designed by famed trail boss Charles Goodnight in 1866. At the rear of the wagon was the chuck box, seen here. It had drawers and cubbyholes similar to a Victorian desk, and stored food, coffee, and the cook’s supplies, among other necessities. Every item and every person on a cattle drive had a role to uphold to ensure their safety and the success of a drive. They depended on the communal chuck wagon—and each other— to survive the long drives through the Western frontier.

Gib Singleton

American, 1935–2014

Blackjack Ketchum

2005

Bronze (12/25)

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

The notorious Hole-in-the-Wall Gang of the late 1800s was not one large organization. Rather, it was a disheveled community of several different outlaw gangs of the American Wild West. Their ideal hideout was a remote location in Wyoming named after its geographic indicator, an eroded hole in the wall of a mesa. The location was difficult to reach— at least one day’s ride from civilization. The narrow passages made it easy to defend, and its panoramic views made it easy to see incoming threats. There was no one leader of the Hole-in-the-Wall camp. Each person adhered to their own gang’s chain of command, though the community did have infrastructure, cabins, an unofficial coalition, and unwritten codes of conduct.

Among those to seek refuge at this camp was Thomas “Black Jack” Ketchum (1863–1901) and his gang, depicted here by artist Gib Singleton. Black Jack was a cowboy who later became a train robber and murderer in the Southwest’s Four Corners region. He was known as a hard man with a deadly shot. After a train robbery gone wrong, Black Jack was captured and executed. Acknowledging the darker side of the West, the artist said, “The outlaws and villains were part of it too. You can’t have good guys unless you have bad guys to compare them to.”

Sculptor Gib Singleton was mostly known for his spiritual art. He was inspired by scripture and interpreting sacred stories using sculpture. Growing up in cowboy boots on a cotton farm in Missouri, Singleton also related to the profound, emotional stories found in the narratives of the West. His life was not short of struggles, and he felt compelled to help better others through his art, which he described as “emotional realism.”

Jim Vogel

American, born 1964

A Time for Every Purpose

2007

Oil on panel

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

The paintings of Jim Vogel typically depict the life and land of his home state, New Mexico. If you study this painting from left to right, you will see that it begins with irrigation. This is fitting, as attempts to control water in the arid desert have shaped human societies in the region for the last twelve thousand years. The practice of complex irrigation and flood control began with the Ancestral Pueblo people, dating back to at least 700 CE. This development allowed for agriculture, making permanent settlements possible.

Until the American government took control in 1848, the people maintained a community-based irrigation practice, sharing water and the responsibility of canal and ditch maintenance. This concept was not welcomed by the American government, whose rhetoric was deeply rooted in independence, individualism, private property, and ownership. It was not long before big business and powerful government took control of the water and agricultural projects.

One thing that has surely stayed the same, is the attempt at domesticating the desert. Making the desert habitable requires a lot of manpower. As suggested in this painting, A Time for Every Purpose, every drop of water, every crop, and every resource available in New Mexico is made possible by the average working men and women.

Vogel is passionate about telling these stories of New Mexico’s culture and community trade through the eyes of the common working man. He uses dynamic colors, flowing compositions, irregular shaped frames, and exaggerated figures to bring marvel to the modest activities of daily life.

Men’s Warrior Collaborative Concho Belt

2014

Sterling silver, various stones, leather

Women’s Inspiration Collaborative Concho Belt

2014

Sterling silver, various stones, leather

Art Spotlight

By: Emily Kapes | Curator of Art

The annual Santa Fe Indian Market is a long weekend celebration and sale of Native arts. Organized by the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA), the August art fair draws hundreds of thousands of Native art admirers from around the country. More than 1,200 artists set up outdoor booths to showcase their art, and the community of Santa Fe, New Mexico, comes alive with parties and gallery openings*.

One of the premier events during Indian Market week is the SWAIA Gala and Live Auction, with sale proceeds benefitting the mission to support the Native artist community. In 2014, select artists were asked to each create an individual concho for themed belts to be auctioned at the event. The culmination of efforts resulted in the stunning work you see here: The Men’s Warrior Collaborative Concho Belt and the Women’s Inspiration Collaborative Concho Belt. Tom and Mary James attended the gala and purchased the two belts with museum display in mind. Each beautiful concho has a story of its own, but put together, the collaborative community of artists came together to create two unique masterpieces.

Contributors to the Men’s Warrior Concho Belt:

Allen Aragon (Navajo), Derrick Gordon, Sr. (Navajo), Tim Herrera (Cochiti), Ivan Howard (Navajo), Alfred Joe (Navajo), Sunshine Reeves (Navajo), Alex Sanchez (Navajo), Cody Sanderson (Navajo), Olin Tsingine (Hopi/Navajo), Lyndon Tsosie (Navajo), and Kee Yazzie, Jr. (Navajo).

Contributors to the Women’s Inspiration Concho Belt:

Keri Ataumbi (Kiowa), Veronica Benally (Navajo), Jennifer Curtis (Navajo), Fritz Casuse (Navajo), Marian Denipah (Navajo/Ohkay Owingeh), Jolene Eustace (Zuni/Cochiti), Carlton Jamon (Zuni), Bryan Joe (Navajo), Kenneth Johnson (Muskogee/ Seminole), Sam LaFountain (Chippewa), Jacob Morgan (Navajo), Verma Nequatewa (Hopi), Eric Othole (Zuni/Cochiti), Myron Panteah (Navajo), Shaax’Saani (Tlingit)

Liz Wallace (Maidu/Washoe/Navajo), and Robin Waynee (Saginaw Chippewa).

*Due to COVID-19, the 99th annual Santa Fe Indian Market has been cancelled for August 2020. The market plans to return in 2021.

Wilson Hurley

American, 1924–2008

Spring Light and Ancient Shadows, Canyon del Muerto

1985

Oil on canvas

Art Spotlight

By: Jason M. Wyatt | Collections Manager

Throughout his career, artist Wilson Hurley painted eight works depicting the famous Mummy Cave ruins located in Canyon del Muerto. This piece titled Spring Light and Ancient Shadows, Canyon del Muerto was the largest of these works. When seen in person, the size and the perspective in which it was painted gives the viewer a firsthand experience of what it would be like seeing these ruins from the canyon floor. Canyon del Muerto is a northern offshoot canyon in the larger Canyon De Chelly National Monument on the Navajo Nation lands in Arizona.

The earliest occupants of the monument area were hunter-gatherers using the canyons as temporary campsites while they followed migrating herds. Around 200 B.C. the introduction of agriculture brought the need (and opportunity) for a more sedentary lifestyle. Small communities began to pop-up throughout the canyon systems and by the 4th century A.D. permanent structures were being constructed.

Based on tree ring dating (dendrochronology), the earliest structures in the Mummy Cave date to between 340-350 A.D. For the next 1000 years, humans occupied the cave, adding more rooms to existing structures. The final structure built is the three-story tower seen in Hurley’s painting near the opening of the cave on the right. A wooden beam from this structure dates the tower to 1284 A.D. The architectural style of this tower is very similar to structures in nearby Mesa Verde, abandoned around 1250 A.D. It is now widely accepted that migrants from Mesa Verde made their way to Canyon del Muerto and settled in the Mummy Cave complex, only to abandon it around 1300 A.D.

It is impossible to know the social, political, and religious ideology of the earliest communities that lived in the Canyon de Chelly National Monument because they left no written records. Anthropologists have speculated that later communities from about 1100-1300 A.D. may have been similar to modern Pueblo groups. These similarities may have included a recognition of descent through matrilineal lines, large extended families living together, and the use of kivas for political meetings and religious ceremonies.

Dave McGary

American, 1958–2013

The Emergence of the Chief

2004

Painted bronze (12/50)

Art Spotlight

By: Jason M. Wyatt | Collections Manager

The Mohawk nation is one of six members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, more commonly called the Iroquois Confederacy. The confederacy is governed by the Grand Council which is made up of fifty leaders. These leaders, called Hoyaneh, are the clan chiefs from each of the six nations. The Mohawk nation is represented by nine Hoyaneh, chosen by the Clan Mothers. In Dave McGary’s sculpture, a Mohawk Clan Mother holds a wampum belt, a symbol of her position within the community. She is shown with her choice for Hoyaneh, based on his ability to put the interests of his people first.

All the nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy are made up of extended family groups called clans. When the confederacy was founded, a new system of nine clans was created named after mammals and birds. Each nation is made up of a different number of clans. For example, the Mohawk nation consists of three clans, while the Oneida nation is made up of all nine clans. Members of a clan are considered related no matter the nation to which they belong. This system was put in place so that same clan members of different nations would develop familial ties in hopes of keeping the peace between the six nations.

All clans follow matrilineal descent, meaning children belong to their mother’s clan. Women hold important positions in matrilineal societies. Among the Haudenosaunee, Clan Mothers are chosen to be head of the clan. Traditionally this was given to the oldest woman in the clan, but now a woman is chosen by clan members based on her cultural knowledge and her dedication to the Haudenosaunee people. Along with the ability to choose a Hoyaneh, Clan Mothers are responsible for making all of the important decisions that affect the clan, naming the newborn children, and making sure everyone in their clan has food. Clan Mothers also have the ability to remove a Hoyaneh if they feel he no longer is representing their nation well.

Books

The James Museum Book Club Recommends…

The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present

by David Treuer

Instead of disappearing, and despite – or perhaps because of – intense struggles to preserve their languages, cultures, and families, American Indians are forging new paths. David Treuer (Ojibwe) has written a hopeful book that’s part history, part journalism, and part memoir reflecting on life growing up on Minnesota’s Leech Lake Reservation.

The title is meant to stand in contrast to the classic book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, in which Dee Brown wrote that “the culture and civilization of the American Indian was destroyed.” That’s not what ended up happening, Treuer says.

To make his point, Treuer tells the stories of people such as Sean Sherman, founder of the Sioux Chef, who is teaching people to cook with traditional ingredients, and tribes such as the Tulalip, who have turned capitalism to their advantage.

Treuer says, “We are using modernity in the best possible way: to work together to heal what was broken.”

Learn more about author David Truer and his brother Anton Truer

Traditionally, movies and books about Native American life have focused on tragedy and defeat. Now, a new work of history and reporting urges readers to consider a more complex culture that is not only still living but evolving. Jeffrey Brown sits down with David Treuer, author of The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee.

A TEDx Talk by Anton Treuer, David’s brother, author of Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians but Were Afraid to Ask. He gives us a focused look at mascots, microaggressions, and helping Native Americans thrive.

Movies

Enjoy feature length and short films that celebrate the power of community.

Feature Films

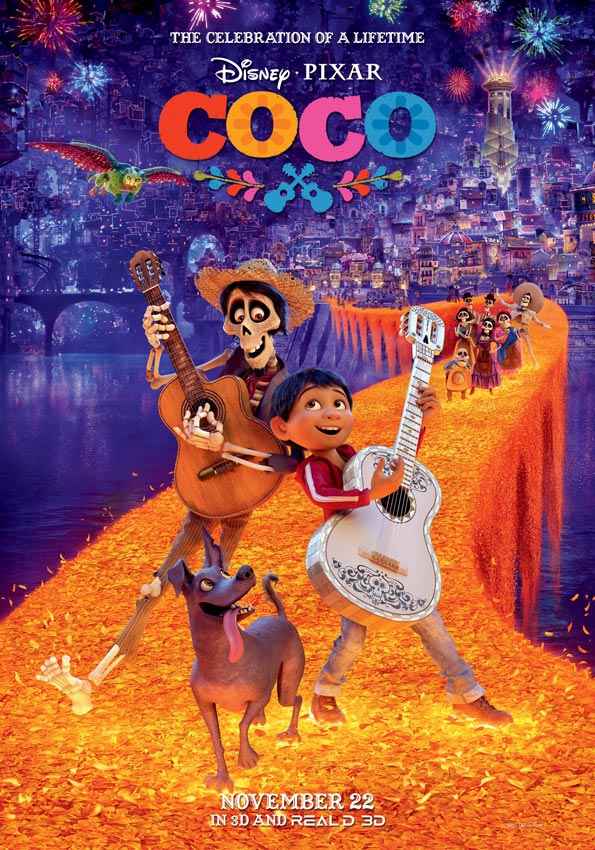

Coco (2017)

In this vibrant tale of family, fun and adventure, an aspiring young musician named Miguel embarks on an extraordinary journey to the magical land of his ancestors. There, the charming trickster Hector becomes an unexpected friend who helps Miguel uncover the mysteries behind his family’s stories and traditions. Rated PG; 109 min.

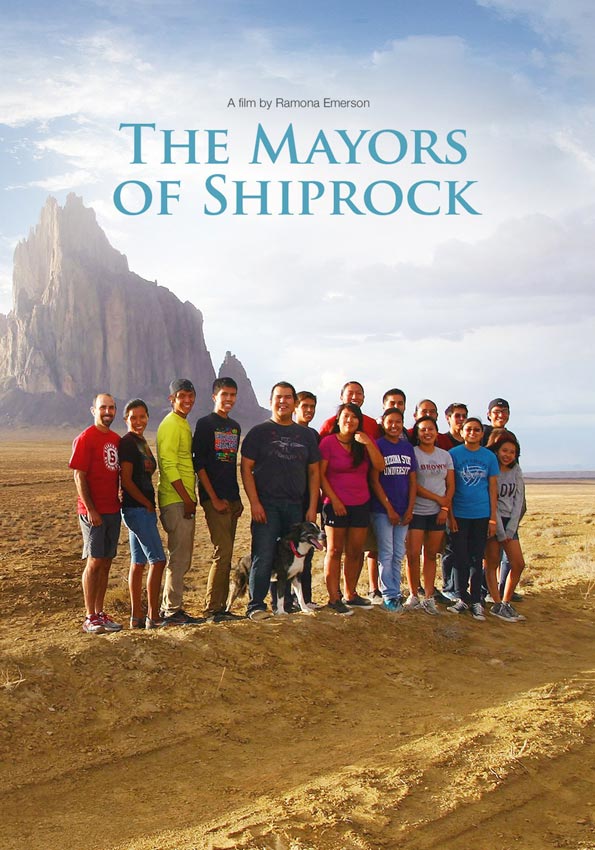

The Mayors of Shiprock (2017)

Every Monday, in the small town of Shiprock, New Mexico, a group of young Navajo leaders meet to decide how they will help their community. Members of the Northern Diné Youth Committee cut and deliver firewood to elders, paint over graffiti, create drip irrigation systems for horticulture, pursue higher education, and inspire their community to dream of a positive future. NR; 57 min.

Short Films

Poet Marshall Davis Jones eloquently reminds us how connected all of our lives are by the human experience. (3:22 min)

Kayla Briët creates art that explores identity, self-discovery, and community – and the fear that her culture may someday be forgotten. She shares how she found her creative voice and reclaimed the stories of her Dutch-Indonesian, Chinese, and Native American heritage by infusing them into film and music time capsules. (5:56 min)

Artist Yumi Sakugawa guides us through a meditation on life in deep space, in a future where Planet Earth exists only in historic memory. By summoning our connections to ancestral knowledge, Sakugawa leads a slow, restorative voyage to demonstrate that, wherever we are in time and space, we can find solace in simply being Earthlings. (12 min)

Family Activities

Story Time

Read along with these colorful and engaging stories.

A Summer’s Trade/Shiigo Na’iini’

By Deborah W Trotter, Illustrated by Irving Toddy

Hungry Johnny

By Cheryl Kay Minnema, Illustrated by Wesley Ballinger

Round is a Tortilla

By Rosanne Greenfield Thong, Illustrated by John Parra

Art Activity

Get creative with inspiration from artists and artwork in the museum’s collection.

Join and Give

Thank you for being a part of #GIVINGTUESDAYNOW! Because of you, 15 frontline workers will be gifted with a membership to The James Museum. You are helping our community heal.

You can still provide the gift of serenity and peace through art. Donate $60 or more and a frontline worker will be gifted with a membership.