Welcome To

The James Museum from Home

Connect with us through curated content based on our collection. Explore art, movies, books, music, family activities and more. Each theme is freshly considered and developed by our curatorial and education teams. We invite you to discover a new way to experience the museum and learn more about our collection.

Theme: Something Borrowed

Pablo Picasso famously said, “Good artists borrow, great artists steal.” Discover the original artwork —that went on to inspire some of the great artists of today— in our exploration of borrowed imagery.

Selected Artwork

Learn about what links these five works of art to iconic images of the past.

Art Spotlight

By: Jason Wyatt | Collections Manager

Images of James Earle Fraser’s (1876–1953) sculpture End of the Trail have been reproduced countless times in decorative objects, souvenirs and art, from just after its 1915 U.S. unveiling through the present. It has been copied, parodied and incorporated into other artists’ work, making it one of the most recognizable Western sculptures of all time. Many Native American groups have used the image in their material culture as a symbol of resilience against the destructive forces their people have endured over the centuries.

When Fraser was a baby, his father, a railroad engineer, moved the family to the Dakota Territory for work, and as a child Fraser was surrounded by settlers heading West as well as the Dakota Sioux. Growing up, Fraser witnessed firsthand injustices toward the Sioux by the United States government. By the 1880s, settlers were flooding into the territory and turning large tracts of land into ranches and farms. The Sioux were forced from their lands onto reservations, which took up most of what is now South Dakota. Before statehood, the United States government used underhanded tactics to trick the Sioux out of half of their reservation land so it could be sold to settlers. This ensured that the state’s majority of landowners would be non-Native.

These experiences had a profound effect on Fraser, who wrote in his memoir how a trapper once told him that, eventually, Native Americans would be pushed into the Pacific Ocean. He created his first version of the sculpture End of the Trail in 1894 as a subtle symbol of protest to the injustices inflicted upon the Sioux and, in particular, their forced removal from their traditional lands. This early version accompanied the artist to Europe, where he exhibited it in Paris and earned a spot at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. The sculpture was not shown in the United States until 1915, when a reworked monumental plaster version was unveiled at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. There it won both critical acclaim and a gold medal. By 1918, Fraser was offering two sizes of the sculpture for sale in bronze.

In 1991 artist John Nieto painted Not Necessarily the End of the Trail (After Fraser) using an image of Fraser’s original bronze sculpture, rendering it in bright colors and setting it against a bleak, characterless background. By turning Fraser’s original somber image into a bright array of colors, Nieto has transformed it into a more optimistic symbol of hope and resilience. The use of colors has brought the image into the modern era, when protests for Native rights no longer need to be subtle but can be robust and take center stage. Nieto’s painting successfully embodies this idea by loudly stating Native Americans’ resilience to past atrocities and their hope for the future.

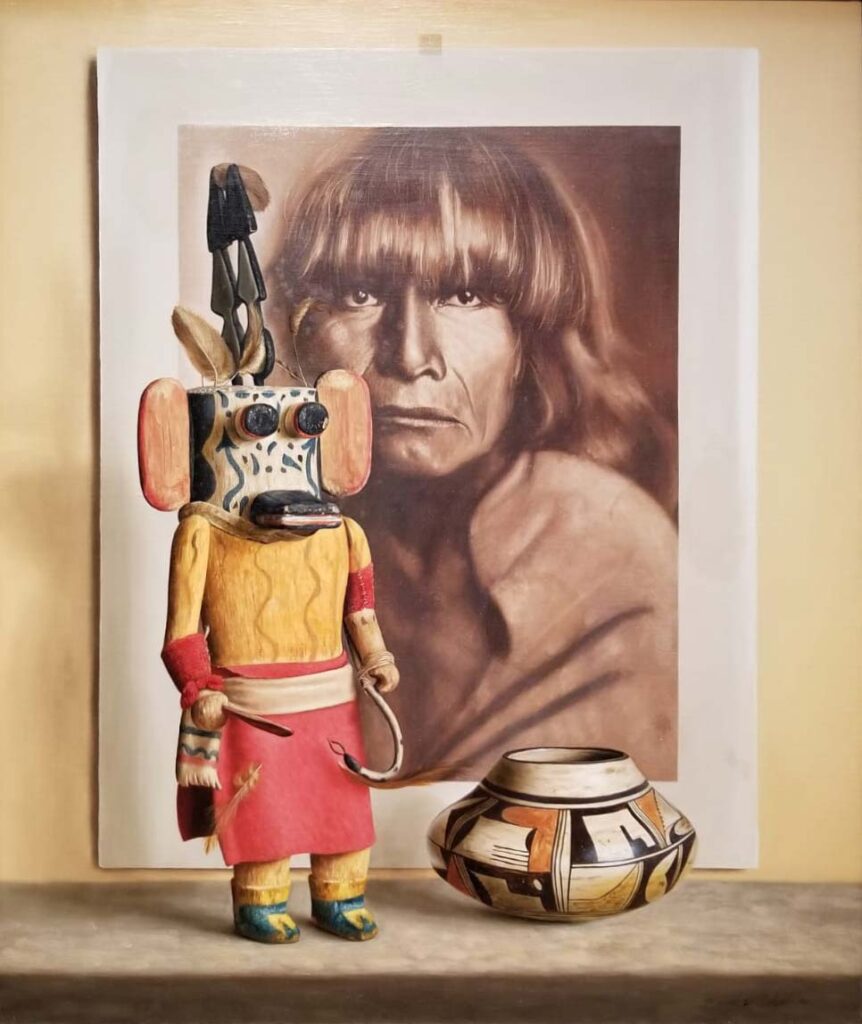

William Acheff

E.S. Curtis – A Hopi Man

1981

Oil on linen

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

Artist William Acheff was first inspired to include a work of art within one of his paintings in the 1970s after seeing Edward Curtis photographs. He thought, I bet I could paint that. He has been borrowing images from other artists ever since, creating trompe l’oeil-style still life paintings, mostly composed of Native American objects.

For this composition, Acheff includes three objects — a katsina carving, a photographic print, and a pot — all loosely tied together with a Hopi theme. The Hopi (“Peaceful People”) are descendants of an ancient civilization, and today the Hopi tribe is a sovereign nation located in modern-day Arizona. Depicted in this painting is a Hopi katsina. These carvings are a significant part of Pueblo culture. This particular katsina is holding an Avanyu, or water serpent, a symbol of the water or rain that is vital for all life existence.

The print in this painting is of a 1904 photograph by Edward Curtis, titled A Hopi Man. In Acheff’s rendering we even see the piece of tape holding the print in place. To achieve such a high level of realism, the artist says he is able to analyze and break down what he is seeing into lights, shadows and colors, rather than whole objects. His work attempts to transcend stillness and evoke a sense of story and serenity. He is known to practice Transcendental Meditation while painting in his studio, which possibly contributes to his work.

According to Acheff, the pot in the painting was most likely created pre-1900 by renowned Hopi-Tewa potter Nampeyo (c. 1859–1942). She was the first potter to become recognized by name outside of the Hopi community, though she did not sign her work. This makes identifying her pottery particularly difficult and has given collectors and dealers a strong incentive to attribute Hopi pottery to her, whether they are certain or not. Nampeyo is famous for her Sikyatki Revival-style pottery. She visited the ruins of the ancient village and copied the prehistoric designs from their pottery, reproducing them on her own vessels. Just as Acheff is doing in this painting, Nampeyo also borrowed imagery.

To further contribute to the story that these three objects tell when arranged together, Nampeyo and Edward Curtis were personally linked. Curtis photographed Nampeyo numerous times when visiting her village and wrote of her in Volume XII of The North American Indian. Most notably, she can be found in his photographs titled The Potter (Nampeyo), Nunipayo Decorating Pottery and Potter Building Her Kiln.

Art Spotlight

By: Caitlin Pendola | Curatorial Associate

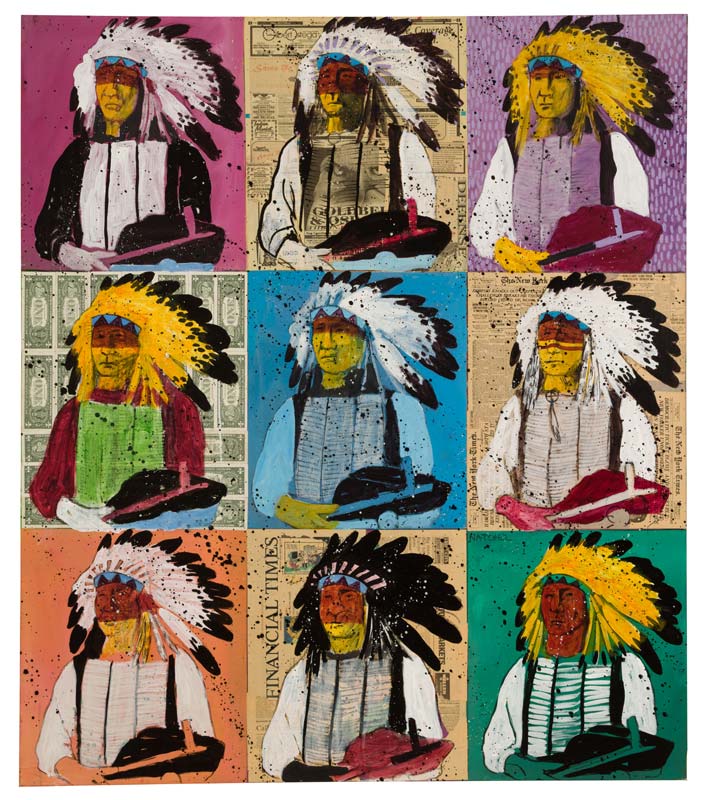

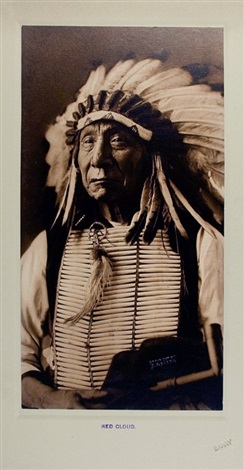

The use of borrowed imagery is at the core of Pop Art. In this work, Tataviam artist Stan Natchez borrows an image by photographer David F. Barry (1854–1934) titled Red Cloud (Mahpiya Luta) in 1887. During the height of Barry’s career in the late 1800s, he traveled to military outposts and American Indian reservations, photographing soldiers and Lakota warriors. This image of Red Cloud, along with several other photographs by Barry, became iconic and have been used extensively in varying media over the centuries.

Here, Natchez translates the recognizable photograph into a Pop Art painting. By combining the post-modernist style with this subject matter, the artist makes an ironic reference to Native identity and resistance. He attempts to erase the noble savage while simultaneously using one. Traditional representations of Native American subjects by artists such as Barry have served to reinforce stereotypes of Native peoples and culture. To challenge these stereotypes, Natchez uses bold color, flattened space and splashy applications of paint to bring to consciousness that American Indians are modern peoples.

It is fitting that he uses Red Cloud, the famed Oglala commander and politician, as a symbol of resistance. During his life, Red Cloud was a national symbol of Lakota resistance against white invasion. By repeating the image and using bold colors, it transforms Red Cloud’s status from famous historical warrior to modern-day celebrity.

To further comment on America’s past and present, Natchez borrows American currency and newspapers, objects he sees as symbols of everyday modern power. According to the artist, “In the 1700s and 1800s, Indians painted on deerskin, buffalo or elk hides. And if you wanted something, hides were your money. So the modern-day hide is the dollar bill.” Like Andy Warhol and other Pop Art artists, Natchez wants the viewer to recognize and question the power of objects.

The artist has stated that this painting refers to treaties that were repeatedly broken by the United States government. Expressing his views and identity in a creative way that is educational rather than combative, he hopes to initiate a healthy dialogue between the two cultures.

By borrowing from David F. Barry, Andy Warhol, Red Cloud and American objects, and bringing them together on a canvas, Natchez produces an original work of art that thoughtfully speaks to the overlapping dichotomy between Native and white relations.

Art Spotlight

By: Emily Kapes | Curator of Art

Mandan chief Mato-Tope (1784–1837) fiercely battled enemies and bravely guided his people. He earned his name, which translates to “Four Bears,” after charging the Assiniboine tribe during battle with the strength of four bears. His impressive wartime victories and tribal leadership captured the attention of Swiss expedition artist Karl Bodmer (1809–1893) during his westward travel to visually document Native cultures and leaders. While in present-day North Dakota in 1834, Bodmer spent time with Mato-Tope in his Mandan village and painted his full-length portrait. It became one of his many significant renderings, decades before photography would become common. Bodmer’s accurate portrayals of Native Americans and Western landscapes were widely published for unfamiliar audiences in the Eastern United States and Europe.

This background sets up the story behind the 2005 sculpture Mato-Tope, Four Bears. For the last 25 years, Arizona artist John Coleman (b. 1949) has dedicated his career to sculpting and painting 19th century Native figures and types. Between 2004 and 2010, he created the Explorer Artists series — 10 bronze sculptures of Native leaders, including Mato-Tope. The full-length, two-dimensional portraits by Bodmer — and another expedition painter of that same time, George Catlin (1796–1872) — served as the basis for the series, with considerable added research by Coleman. He created the sculptures not to add or take away from those original visual documents, but to faithfully pay tribute to the artists and those who posed.

In Coleman’s version, Mato-Tope stands with the same profiled stance and with many of the details in Bodmer’s rendering. The leader is adorned in his finest clothing with accoutrements from past victories of war. The wooden knife in his war bonnet is a reminder when a Cheyenne warrior wounded Mato-Tope’s hand in battle. Mato-Tope disarmed him, however, and kept the knife. The lance in his hand was used to kill an Arikara who had murdered his brother, and was further adorned with the enemy’s scalp. With a bit of artistic license, Coleman’s sculpture takes the pose to the next level. He formally accentuates Mato-Tope’s high-held head and proud posture, more so than in Bodmer’s more reserved version. Coleman’s interpretations of the paintings of Bodmer and Catlin in his Explorer Artists series have spotlighted the significance of the original work for current generations of contemporary Western art appreciators.

Art Spotlight

By: Jason Wyatt | Collections Manager

It is generally accepted that the first Western narrative movie created is The Great Train Robbery from 1903. In this 12-minute movie, the bandits dressed in black rob a train, are chased by a posse, and die in a shoot-out. These themes would become the basis of many celebrated Westerns produced in Hollywood.

As Western movies became more popular, so did their influence on society’s concept of what the West was like before the 20th century. People perceived the West as filled with good guys dressed in white and bad guys dressed in black. Other common, extreme notions included Native Americans as either drunks or savages, and women who were either prim and proper teetotalers or floozies in saloons.

These Hollywood stereotypes eventually found their way into the Sunday comics, pulp fiction, television, children’s toys and other aspects of popular culture. As more illustrators turned their talents toward the world of fine arts, they carried these stereotypes into that world, too. Artist-adventurers such as Karl Bodmer and George Catlin, who depicted the West from firsthand knowledge, were pushed aside in favor of artists like the founders of the Cowboy Artists of America, who portrayed the West through a Hollywood lens.

Hollywood’s influence on Western art has continued into the 21st century. In 2012, Andy Thomas painted this work titled Shot of Vengeance that features the main character turning back to fire a shot as he flees down the main street of a Wild West town. The artist’s main character is a portrait of actor Lee Marvin (1924–1987) playing Liberty Valance in the 1962 classic Western movie directed by John Ford, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. In that movie, Valance is an outlaw hired by cattle barons to terrorize the frontier town of Shinbone so they can ensure their own interests succeed. This character becomes a symbol of everything that is wrong with the Wild West, and his blatant disregard for human life and the law eventually help propel the unknown territory toward statehood. Valance always appears in his black hat and waistcoat, a sure sign he is the Bad Guy. Drawing upon this stereotype, the artist leaves no question in the viewer’s mind that these are villains fleeing in a classic shoot-out.

Book Recommendation

The James Museum Book Club Recommends…

Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis

by Timothy Egan

Learn More

Northwestern University Library presents a digitized collection of The North American Indian by Edward S. Curtis.

Author and New York Times columnist Timothy Egan tells the epic story of Seattle photographer Edward Curtis.

A collaborative project to restore, re-evaluate, and re-frame Edward Curtis’s 1914 film, In the Land of the Head Hunters. The film was reunited with its original orchestral score and informed by descendants of the original Kwakwaka’wakw cast.

Movies

Enjoy two classic Westerns that show how creativity and inspiration can flow from canvas to film and back again.

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949)

Filmmaker John Ford (1894-1973) was inspired by the work of artist Frederic Remington (1861-1909), whose romanticized, action-packed paintings and bronze sculptures imprinted an image of the Old West on the American imagination. About his 1949 movie She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Ford said “I tried to copy the Frederic Remington style.” Shot in Technicolor, it is a departure from Ford’s earlier black and white Westerns, featuring a richer-than-life palette that evokes the vivid reds and browns of Remington’s paintings.

The Academy Award winning movie was the second in Ford’s cavalry trilogy – the other two being Fort Apache (1948) and Rio Grande (1950). With a budget of $1.6 million, it was one of the most expensive Westerns made at that time. Shot on location in Monument Valley, located on the Navajo Nation near the Arizona-Utah border, it won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography in 1950. She Wore a Yellow Ribbon was a solid box-office hit when it was released, and today is regarded as one of Ford’s finest.

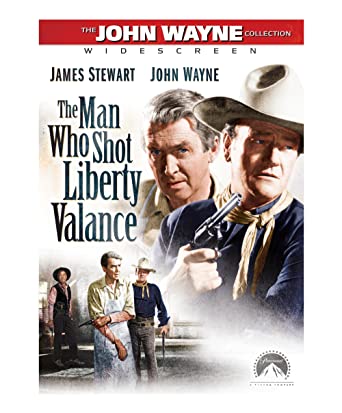

The Man who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

John Ford’s 1962 movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence is a poetic and somber look at the end of the Wild West. It is widely considered Ford’s last great movie and among his best Westerns.

When idealistic young lawyer Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart) arrives in town, he is determined to remove the menace posed by the brutal, murderous bandit Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin) by putting him in jail. The ace gunfighter Tom Doniphon (John Wayne) scoffs at Stoddard for being a city slicker who doesn’t understand how things work on frontier and advises him to get a gun. But the movie takes Stoddard’s side and makes the case that accepting the rule of law rather than bowing to raw displays of power is how a town becomes modern.

Inspired by the paintings and sculptures of Frederic Remington, filmmaker John Ford’s classic Westerns have also served as a source of inspiration to other artists. In fact, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence is the subject of a painting by Andy Thomas, titled Shot of Vengeance (2012). You can see it in the James Museum’s Frontier Gallery.

Find inspiration through a story and get creative with a hands-on art project.

Family activities

Find inspiration through a story and get creative with a hands-on art project.

Art Look & Book

Uncle Andy’s

By James Warhola

Join us on Oct. 21st at 10 a.m. for a kid-friendly look at a work of art followed by a story. This month’s book is Uncle Andy’s by James Warhola. Learn about playful pop art and meet a young boy who gets inspired by his uncle’s colorful creations.

Best for ages 3-7. Register at least 24 hours in advance to receive a Zoom meeting link to attend.

Mini Maker Space

Shaving Cream Prints

Follow along from home on as we make a simple and creative art project. This month we make colorful shaving cream prints! Gather these materials in advance: shaving foam, shallow baking dish, watercolor paint, stir stick, card stock paper, and a small piece of cardboard.

Best for ages 3-7.